The closest Paris-Roubaix of all-time*

Plus a new episode for Friends of the Podcast is online now

Coorevits Corner and a trip to the museum

by Lionel Birnie

The morning after the Tour of Flanders, I headed to Roeselare to meet Hugo Coorevits, the recently-retired journalist who covered cycling for more than three decades.

He started his sportswriting career at Het Volk before moving to Het Nieuwsblad – newspapers synonymous with cycling because they founded two of Belgium's biggest one-day races, Omloop Het Volk (later renamed Omloop Het Nieuwsblad when the two papers merged), and the Tour of Flanders.

Hugo suggested we meet at Koers, the museum dedicated to cycle sport, where we were given a guided tour by Dries Mombert, a former cycling journalist, who curates the exhibits.

Over the course of a couple of hours, Hugo and I talked about his career covering the sport and Belgian cycling in general as we perused the bikes, jerseys, trophies and other memorabilia on display.

The museum features a permanent memorial to one of Roeselare's favourite sons, Jean-Pierre Monseré, who was the prodigy of his day, winning the road world championships in Leicester in 1970 at the age of 21. Tragically, he was killed the following March while racing a small kermesse race near the Dutch border.

Our producer Adam Bowie has done a great job cutting our freewheeling conversation down to an hour for the latest Friends of the Podcast special episode, which is online now. It's called Coorevits Corner.

By subscribing as a Friend of the Podcast you get access to an archive of more than 300 special episodes made over the past decade and the financial support makes a huge contribution to ensuring we can keep our regular episodes free for all to enjoy.

If you sign up as a Friend of the Podcast you can add the feed to your preferred podcast player in a few easy clicks. If you choose to use Spotify the free and Friends feeds are combined so you can listen to all our episodes in one place.

Photos

• Hugo Coorevits on the Paris-Roubaix pavé taken by his daughter Gretel Coorevits

• The Koers museum with the statue of 1970 world champion Jean-Pierre Monseré

• Jerseys as part of the display marking 40 years of the Lotto team’s sponsorship

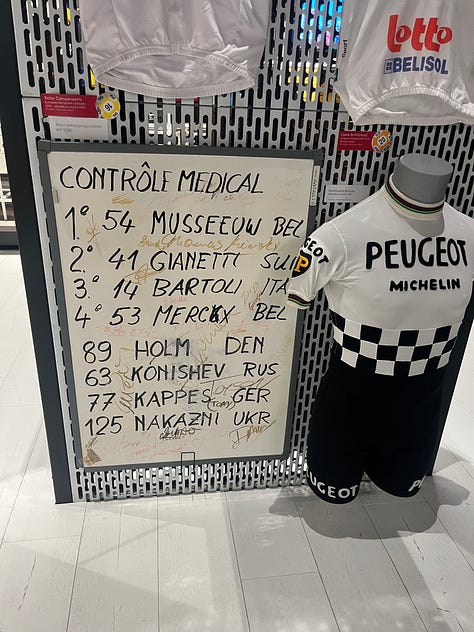

• The doping control whiteboard from the 1996 world championship road race in Lugano

• Medication packaging banned, permitted with a TUE and legal

• Rodolpho Muller’s 1903 Tour de France bike

• An early 1990s time trial bike ridden by the Panasonic team

• Peak Roger De Vlaeminck in a sheepskin coat, by legendary photographer Maurice Terryn

• The best 11.01 cappuccino I’ve ever had, with a mini ice cream on the side

Arrivée from the velodrome

The Hell of the North, the Queen of the Classics, whatever you choose to call Paris-Roubaix it is one of the best days of the cycling year and we will be releasing two episodes of Arrivée over the weekend to recap all the action.

Rose Manley and Denny Gray will be in the velodrome on Saturday for the fifth edition of Paris-Roubaix Femmes and Lionel will be there on Sunday for the men’s race, where he’ll dial up Daniel for our first take on the action.

This week’s regular episode with Daniel, Lionel and Rob Hatch is called Old Pog, New Tricks and looks ahead to Tadej Pogačar’s debut on the pavé as he makes his senior Paris-Roubaix debut. We also tie up the loose ends from the Tour of Flanders and mark the Lotto team’s 40th anniversary.

Classic Tales part four: The 1990 Paris-Roubaix

I wrote this piece in 2010 to mark the 20th anniversary of the closest Paris-Roubaix finish of all-time, when there was a photo finish in the velodrome between Eddy Planckaert and Steve Bauer. Of course, the 1949 edition was technically closer because Serse Coppi and André Mahé were declared joint winners after Mahé had been directed off course by an official as he approached the velodrome. Coppi and Mahé finished separately, split by a group of other riders, but in the chaos and controversy the jury decided to make them joint winners.

by Lionel Birnie

As soon as Eddy Planckaert and Steve Bauer crossed the line in the Roubaix velodrome they glanced across at each other. Neither of them was prepared to claim victory and, as it turned out, both riders had hit the line with their eyes tightly shut anyway.

And if they didn’t know who’d won, it was unlkely anyone in the velodrome would be able to split them. Instead of a cheer, there was a suspense-filled ‘ooh’ as the two riders hit the line side by side, followed by a rising murmur of debate. Even the voice of the commentator, which had been pumping out of the loudspeakers around the velodrome all afternoon, went quiet. He didn’t know who’d won either.

For more than ten agonising minutes the blazered members of the race jury scrutinised the photo finish pictures in a little hut at the back of one of the stands. The technology was up-to-date for 1990, though nothing spectacular by current standards, but it was all they had to go on. A slightly grainy, freeze-framed, black and white picture of the split-second the front wheels of Planckaert’s Panasonic-branded bike and Bauer’s Eddy Merckx hit the line. It took plenty of deliberation and even with the photograph and the straight-edge of a ruler it was difficult to tell, but eventually they agreed and the head judge, a man named Joel Menard, announced their decision.

The Belgians in the crowd, and there were plenty of them, cheered. Planckaert collapsed into the arms of his sports director – who happened to be his older brother, Walter – and Bauer slumped onto the grass in the centre of the track, consoled by the helpers from his team. Damn, that was close. Eddy Planckaert had won Paris-Roubaix, the most demanding single-day bicycle race in the world, by less than a centimetre.

‘It was a beautiful, beautiful day,’ he says. ‘It was more beautiful for me to win by a few millimetres than if I had won alone, five minutes in front of the next rider, because everyone remembers it.’

* * *

Planckaert always felt he was destined to win Paris-Roubaix and become the first of the three cycling brothers to bring home one of those cobblestones as a trophy. Willy, 14 years older than Eddy, had been fourth in 1966 and Walter, ten years Eddy’s senior, equalled that in 1973. But time was beginning to run out for Eddy to put the Planckaert name on the roll of honour of a race known as the Queen of the Classics. He was 31 and probably had a good few years left in him, but a couple of fifth places were the closest he’d managed to get. Every time something went wrong. A puncture, a crash, a moment’s inattention.

For the 1990 season he had returned to Peter Post’s Panasonic team after two years with the ADR squad. Panasonic had a team packed with powerhouses and, with the fall of the Berlin Wall allowing riders from Eastern Europe to turn professional, Post had been quick to snap up East Germany’s Olympic champion Olaf Ludwig and Russia’s Vjatcheslav Ekimov. Panasonic also had the defending Paris-Roubaix champion, Jean-Marie Wampers, another Belgian in their line-up. Post, as usual obsessed with victory, told his riders that they had so much talent in their team that it would be tantamount to a crime if they were not to win.

Planckaert woke up that morning and felt strong. In fact, he’d felt good all week. The previous Sunday, a puncture just before the Oude Kwaremont ruined his chances of a second Tour of Flanders victory. And although he didn’t want to go too deep during Wednesday’s Gent-Wevelgem he was finding it surprisingly easy to follow the wheels and he barely felt the cobbles. Another puncture eliminated him from the final showdown. As he ate his breakfast on the morning of Paris-Roubaix he joked that he was owed some luck.

* * *

Like Planckaert, the Canadian Steve Bauer was built for Paris-Roubaix. He was stocky and strong and he ate up the cobbles. Although he wasn’t brought up among the fields of Flanders or northern France and the region’s broken roads, he felt comfortable there. Ever since turning professional, Paris-Roubaix appealled to him and he had made his home in Belgium so the roads were all familiar. In 1988 Bauer finished eighth in Roubaix, a result that gave him the confidence to believe he could one day win it. Later that year he finished fourth in the Tour de France, but the week of the three big cobbled Classics still motivated him and was the big target of the first part of his season.

‘The cobbles always suited me,’ he says. ‘I’ve got a small frame, not too tall, but muscular, I guess a low centre of gravity, and I rode a small frame too. For Paris-Roubaix I had a bike with a long wheelbase with the saddle pushed back a little so I could use the hamstrings a bit more, keep the big gear going. It was like a Cadillac on the cobbles. I had a pretty smooth pedal stroke so that helped too.

‘I always targeted that week, and I felt good. I’d gotten round the Tour of Flanders okay, and I was good at Ghent-Wevelgem [he was ninth]. On the Thursday I rode five hours, did most of the Paris-Roubaix course.’ Bauer knew the way. He had a good sense of direction and an eye for detail. ‘I was a fast learner and my friends used to call me “compass head”. Even now, if you put me on my bike, I could probably ride that course off the top of my head.’ It came naturally to him to memorise the perfect racing line. ‘There was one notorious section you turn left onto, I forget the name of the sector but I can picture it now, and if you go too wide you end up in this trough where you can puncture or even break a wheel. It’s deep, so you have to be in the centre. It was better to lose a few places going into that corner than take it wide and crash or break something. Another thing, at Arenberg, after 100 metres, there was a section in the middle where four or five cobbles are just missing. It’s a crater, but you had to nail it down the centre, you can’t go on the edges in Arenberg otherwise you lose a lot of speed because it’s even worse there, so you have to jump your bike over the hole. The guys who want to win know these things.’

Both Planckaert and Bauer felt good that April morning and as they rolled out of Compiègne they were already concentrating hard and racing to win. ‘I did everything right that day,’ says Bauer. ‘I stayed in a good position all day and I was patient. I didn’t rush and I chose my moments quite calmly.’

Planckaert, on the other hand, was like a pea on a drum. ‘I felt like Eddy Merckx,’ he says. ‘It was probably the best day I ever had on a bike. I was running away with myself and Post and my brother [Walter] wanted me to wait.’

He was in no mood to be cautious, he knew he had to get his strike in first. Being in such a strong squad, there was the added complication that one of his team-mates might deny him the opportunity. Stephan Joho, a Swiss rider with the Ariostea team, had attacked early on and was joined by Peter Pieters and Rob Kleinsman of TVM. A strong headwind was blowing and, with most of the race heading in the same north-easterly direction, it was going to be in their faces all day. As ever some big names fell by the wayside, and before things really hotted up, two former winners were more or less eliminated, as Eric Vanderaerden punctured and Dirk De Mol crashed.

After the Forest of Arenberg, a group of 20 or so got clear of the bunch. Ominously for the rest, there were five Panasonic riders in it. Planckaert, Wampers, Urs Freuler, Ludwig and John Talen. Post’s team was holding a fist full of kings and aces.

* * *

Jean-Marie Wampers, the reigning champion and Planckaert’s team-mate also felt strong and he fancied his chances of making it two in a row. Wampers was one of those riders who made the cobbled classics his speciality and the memory of arriving in the velodrome and out-sprinting Dirk De Wolf comfortably in 1989 is the defining one of his career. It was the first time the race had returned to the velodrome after a three-year break while the track was resurfaced. From 1986 to 1988 they arrived on a wide boulevard in Roubaix, robbing the finish of some of some of its magic. For Wampers, the moment he entered the velodrome will stay with him for life. ‘It was the first time back on the track and the weather was quite good, so the crowd was huge. They were hanging over the wall and a lot of people were on the grass in the middle of the track, which is usually only for people working on the race. They didn’t have the big television screen in those days so all the crowd knew was what the announcer in the stadium told them. It was like listening to the radio, so when we arrived it was the first thing they’d seen all day, and they went wild. They were so happy to see us, they greeted us like two pop stars.’

Like 1989, the 1990 race was held in bright, sunny conditions. When Planckaert attacked in pursuit of Joho and the other two with almost 100 kilometres to go, Wampers feared it was too early but nevertheless nodded his head at his team-mate’s guile and quietly wished he’d been the one to make such a bold move. ‘I felt so good. I think I was the best guy in the race, honestly, I do. I had such morale from having won the year before and I was so strong.’ Wampers found it frustrating to feel so paralysed. ‘One minus point is that Eddy got in the break before me. I could have attacked first, but Eddy was a smart rider, eh?’ he says. ‘I thought it was too early, particularly to go alone, into the wind, but he knew once he was in front, the four of us would ride for him and protect him. Once Planckaert was ahead, there was no question of doing anything for myself. Post wouldn’t have it.’ Riding against team interests and orders was a big no-no in the Panasonic squad and Post’s retribution could be harsh.

Planckaert caught and eventually passed Joho’s group, but the lead was never huge, a minute or so at most, and on straight sections the Panasonic-packed chase group could see the motorbikes following him up ahead.

Laurent Fignon took up the chase, applying the pressure on the cobbles, and every time a different rider in Panasonic colours sat on his wheel. ‘He attacked twice on the cobbles and he could drive for one or two kilometres at 60 kilometres an hour,’ says Wampers. ‘He was so good. I was lucky because I was strong enough to follow him.’ Fignon didn’t even bother to ask Wampers to contribute because he knew the Panasonic rider was protecting Planckaert.

* * *

‘It’s a methodical race,’ says Bauer. ‘You have to be in the right place at all the important times. I was a good bike handler and I could get into position for the cobbles, that was never a problem but you still had to get it done. Battling from roadside ditch to roadside ditch isn’t for everyone.’

At the front, the Frenchman Martial Gayant, and a relatively unfancied Belgian, Kurt Van Keirsbulck of the Isoglass team, had got across to Planckaert by the time they reached Bersee, with 60 kilometres to go. Until that morning Van Keirsbulck was Isoglass’s reserve and had to quickly get changed and into the right mindset when his team-mate Patrick Hendrikx woke up feeling unwell.

Fignon’s unchained aggression helped Bauer and Panasonic’s other rivals in the group behind Planckaert. ‘I was patient that day, but when the opportunity came, I went for it. Fignon was doing tons of work, he was over-working really, which was great for us because he brought the gap down to something that was manageable,’ says Bauer.

First the lanky frame of Edwig Van Hooydonck and then Bauer went across the gap, leaving Fignon behind. They were surprised none of the Panasonic riders went with them. ‘I countered an attack from Fignon and went boom straight across to the break in really quick time,’ says Bauer.

Van Hooydonck, the red-haired Belgian who had won the Tour of Flanders in 1989, was not having a good day and was riding on wits and know-how rather than pure strength. ‘Two weeks before the Tour of Flanders I was sick, with diarrhoea. I didn’t finish the Tour of Flanders but I managed better in Gent-Wevelgem. I was not super but I was coming better.’

Although he knew he did not have good legs when he woke that morning, his Buckler team manager, Jan Raas, told him he could ride his own race and see how things turned out. Raas and Post, the two Dutch team managers, had a fiercely competitive rivalry that threatened to spill over into spoiling tactics every so often. ‘We were the good guys, right,’ jokes Van Hooydonck. ‘We were the smaller team and Post was obsessed with beating us.’ So Raas was happy to see a rider in a Panasonic jersey win, was he? ‘Ha, ha, I wouldn’t say that. No, no, not at all, but he didn’t say we had to stop them winning first. We tried to win for ourselves. Usually.’

In normal circumstances, Van Hooydonck would have been in his element. As an 18-year-old he had finished in the front group in the amateur Paris-Roubaix, up there with Russians and hardened Belgians, some almost twice his age. And the headwind should have been to his liking too. ‘I liked the wind in the face,’ he says. ‘It encourages the strong to the front and the weak get blown backwards.’

But Van Hooydonck went into the race feeling cautious. ‘Sometimes when you have good legs you do too much in the race, chasing everything, attacking all the time,’ he says. ‘When you are strong you can do stupid things. When you are not strong, you are worried all the time you don’t have much left so you do it easy, easy, easy and you can make a better result of it. That’s how it was that day. It was survival, just try to stay with them, not make too much effort.’

When Planckaert attacked so far from the velodrome, some of his rivals looked at each other and shrugged, Van Hooydonck says. ‘He was either super, super good, or he was going to kill himself.’

* * *

Frightened that there was a big group closing in on the leading six, Bauer wanted to try to get rid of a some more riders, so he launched a severe attack at Camphin-en-Pévèle with around 20 kilometres to go. Then, as now, it is one of the worst sections and Bauer’s move was so strong that even Planckaert, who had looked sublimely smooth, could not react immediately.

The Belgian did not panic. ‘Bauer was very classy, he was a good boy, but it was important for me not to do anything silly.’ Planckaert took his time to ride over the gap without extending himself into the red. Van Hooydonck, feeling tired by now, made more of a meal of it.

The difficulty so late in the race was having good information. ‘You didn’t have the sport director in the car coming up to tell you what was happening behind,’ says Bauer. ‘We didn’t have race radios, so you got your gaps from the guy on a motorcycle with a chalkboard. You pretty much couldn’t rely on that at all, so you had to race with your sense. You knew there was a group behind, you knew they’d be chasing, so you just kept pressing on.’

Bauer wasn’t too concerned about Van Hooydonck or the possibility of a Dutch-Belgian combine joining forces. There was never any chance of a Panasonic rider helping a Buckler man or vice versa. In fact, Bauer hoped to exploit that little rivalry, and he may well have been able to if Van Hooydonck had been capable of doing anything more than follow. ‘I think he was a little bit on the tired side, but I thought he might counter one of my attacks,’ says Bauer. The priority was to try to shake off Planckaert. ‘Man for man, Planckaert had proven to be faster than me in the sprint. He had been a bunch sprinter earlier in his career, won the green jersey in the Tour, so my tactic was to try to get away, but he wasn’t having any of it.’

Van Hooydonck was hoping for a miracle. ‘I thought if there was a chance to get away very late maybe Planckaert and Bauer would look at each other and hesitate for a moment, but I was very tired and every time Bauer attacked it took me longer to get up to the wheel so I knew my chance was very small.’

Behind them, Gayant was chasing alone, with Wampers leading the next group. Bauer and Planckaert took turns on the front and Van Hooydonck sat on the back. Bauer led them round the right-hand bend through the gates and onto the concrete track and was shocked that Gayant and Wampers were almost upon them. The three riders had gone to the top of the banking, allowing the other two to hug the racing line and draw level with them. The leading three and the chasing pair came together as a group of five, giving Planckaert a teammate, Wampers, to help in the sprint.

‘It was a bit of a surprise, I gotta admit,’ says Bauer. ‘I knew they wouldn’t have given up but I had no idea they were that close. We were up the banking so it wasn’t a real factor, it was easy to get onto them as they came by underneath because it had gotten cagey as we started to think about the sprint.’

One thing Bauer was counting on was that Gayant and Wampers would be tired from the chase, and he was right. Gayant had been out there for a while, and Wampers had plundered his reserves to get across and would only be able to give Planckaert a bit of help. ‘I attacked and Bontempi, Madiot and these guys couldn’t follow me,’ Wampers says. ‘I think that shows I was the strongest of the riders in the second group, but the problem was I had closed about 30 seconds in about 1.5 kilometres, and I did it in one go. When we caught them, they were already on the track and it was too late. I needed just one or two minutes to rest. It was still too far from the finish line, about 650 metres, for me to even think about going straight past them. I wouldn’t have made it. Nor would Gayant.’

Planckaert was pleased to see the red, yellow and blue jersey and he hoped Wampers would lead out the sprint, or ‘spurt’ as he calls it. ‘Wampers went to the front and Planckaert settled onto his wheel but the pace was not high enough. Jean-Marie was tired from the chase and it all slowed down,’ he says. ‘I lost a bit of concentration because when I was on his wheel I thought “okay, now I’ll win this easily, I have a team-mate to lead me” but the pace was not high enough and the others were all moving around me. It was a very strange finish, everything was a bit disturbed and my brain could not compute it. In fact, it would have been better if Jean-Marie had stayed in the back and I had done a normal spurt.’

With his track craft, Bauer was hoping to equalise the difference in pure speed between he and Planckaert, but it was Van Hooydonck who went for the long one, a death or glory bid down the back straight, turning over his weary legs and bobbing his head and shoulders, almost lifting the front wheel off the track with the sheer depth of effort he went to.

As Van Hooydonck rounded the final bend, roughly in the middle of the track, Bauer dived down to take the preferred inside line, leaving Planckaert with no option but to go the long way, over the top of his tall compatriot Van Hooydonck.

‘With one kilometre to go, I was 100 per cent sure I’d win by 10 metres,’ says Planckaert. ‘With 100 metres to go, I was behind and I wasn’t sure anymore. I did the last 20 metres with my eyes closed.’

‘I don’t think Planckaert or I got a good bike throw,’ says Bauer. ‘I had my eyes closed and I was really surprised by the flashes of the cameras, but immediately I was like “shit, I didn’t throw my bike properly”. He didn’t scoop me, for sure.’

None of the riders immediately behind had a clue who had won. ‘I remember a Belgian national junior championship road race [in 1986] once where Wilfried Nelissen and Serge Baguet were so close the organisers made them ride the last one kilometre again, man against man,’ says Van Hooydonck. ‘Of course there was a photo, but I wondered if they would make Eddy and Bauer do another lap of the track if they couldn’t tell.’ Nelissen won that re-run final kilometre showdown for the junior title, but fortunately there was no need for that here.

* * *

Planckaert and Bauer shook hands and went and sat with their team helpers. ‘Someone said to me “Oh you definitely got it,”’ says Planckaert. ‘But I thought “Don’t be crazy”. I know I had my eyes closed but if I didn’t know for sure, and Bauer didn’t know… They were just saying it to make me feel good, I know.’

Wampers says: ‘Everyone in the Panasonic team thought it was Planckaert, but then I looked over to where Bauer was, and everyone in 7-Eleven was saying he’d won, so I thought “oh shit”.’

Then came the moment that brought Planckaert relief and then joy. ‘I saw the picture but it was so close. You can see I won, but it’s a centimetre, maybe even less. I was happy, of course, but even in that moment I felt pity for him [Bauer] to lose a race of 266 kilometres by that. It’s something that will follow you all your life.’

Bauer, though, took the narrowest of defeats with philosophical grace. ‘I did pretty much everything right that day, so I wasn’t going to beat myself up. I was keeping my fingers crossed it was me but I’d done what I could do.’ He didn’t see the picture that day but it didn’t cross his mind to question the verdict. ‘I trusted the photo finish camera and the jury,’ he says. ‘I didn’t check it out in the velodrome, maybe it would have been good to check it out. I saw it a few days later.

‘It is pretty tough to be second but it was an amazing race. My attitude to sport overall was that there are going to be wins and losses, or second places or whatever. The only way you can overcome these defeats is to say “okay, let’s look ahead”. There’s no point wasting energy thinking about something you can’t change.’

* * *

Finally the Planckaert name was among the list of Paris-Roubaix winners and Eddy and Walter shed a tear of joy. ‘I feel it was my day to be like Eddy Merckx,’ he says. ‘I rode 100 kilometres in the front and I won by a centimetre. The Tour of Flanders was a beautiful victory but Paris-Roubaix is the best race to win. Even in America they talk about it. I dreamt about it as a small boy, I won it, and I still think about it now.’

But whenever he sees the finish of that race a little shudder goes down his spine. ‘I think it would haunt me the rest of my life if I had lost by one centimetre. I have seen it many times on TV, hundreds and hundreds of times, probably, and every time I watch it as if it was the first time. I swear, I am frightened that this time I’ll lose.

‘And it’s such a relief when I can go “Yes, I win again”.’

Stacy’s cobbled cups go on sale on Saturday

Stacy Snyder has produced a very limited run of 48 special edition handmade cups to celebrate the cobbled classics and they will go on sale tomorrow (Saturday, April 12). The cups feature a beautiful cobbled detail on one side with Belgian and French colour schemes to signify the Tour of Flanders and Paris-Roubaix.

It is possible this may be Stacy’s only batch of cups for The Cycling Podcast this year. With so much uncertainty regarding tariffs and global trade, Stacy is unable to commit to making batches of cups for the Grand Tours as she has done since 2019. She hopes to make some other batches but at the moment speculation would be unwise.

So, if you would like a cobbled cup, they will go on sale on tomorrow at:

10am East Coast Time, 7am Pacific Coast Time, 3pm British Summer Time, 4pm Central Europe, Midnight Sunday in Sydney from her Etsy store.

Laka – top-notch cover for cyclists

Every ride comes with its risks – whether it’s a stolen bike, a crash, or a broken derailleur at the worst possible moment. That’s why Laka Bicycle Insurance exists.

Laka uses a collective-driven insurance subscription to make bicycle insurance fair, not fixed. Before Laka, cyclists faced long contracts, tons of fine print and robotic customer service. Laka flipped insurance with flexible monthly policies and collective pricing so customers only pay what's needed, not what's expected. Most importantly, Laka processes claims in-house with outstanding, five-star service.

With a community-powered model that means you only pay a fair share each month, Laka is bike insurance done right.

Our listeners get their first 30 days free with code TCP30 at Laka.co/tcp. Ride worry-free with Laka.

Thanks to Laka, our title sponsors for the spring Classics season.

Another enthralling tale. As a young Canadian cyclist, Steve Bauer was a hero to me. That 2nd is agonizing for the national story, yet perhaps fitting for our national character.

Watching Alison Jackson win P-R some odd 27 years later was a redemption of sorts