by Lionel Birnie

Twenty years ago, a group of young lads moved into a couple of shared houses in Fallowfield, to the south of Manchester. The area is home to thousands of students attending the city’s university but these young men were enrolling in the fledgling British Cycling Academy – the University of Life, the School of Hard Knocks, all dreaming of graduating to the Tour de France.

They had been selected by Rod Ellingworth, who had a vision of establishing an academy to develop young riders by giving them the skills to make it in the peloton.

As Rod says in the episode, British Cycling’s system was getting better at identifying and developing riders who could pedal in a straight line – or round in circles – but making it as a professional rider on the road in Europe required a more complete skillset on, and especially off, the bike; adaptability, resilience, self-sufficiency, grit and discipline being near the top of the checklist.

In the first few years of the 21st century, British Cycling’s revolution was in its very early stages. National Lottery funding and the creation of the World Class Performance Plan was beginning to yield results on the track. Jason Queally won a gold medal in the kilometre at the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, Chris Hoy followed him in Athens four years later.

Peter Keen, the architect of the World Class Performance Plan, had designed it to make a rapid impact to first justify and then increase Lottery funding. The focus was on timed events on the track where the goal was quantifiable and progress could be tracked by fractions of a second.

But on the road, British cycling seemed to be going backwards. In 2004, for the first time in almost 30 years, there wasn’t a single British rider in the Tour de France. David Millar, who had made a stunning impact by winning the opening stage of his first Tour de France four years earlier, had been arrested in Biarritz shortly before the grand départ, and confessed to doping. His was a cautionary tale of the isolating nature of life as a young professional in a foreign country. Youngsters were expected to live like monks by pro team management who were often decades older than the riders. The peculiar contradiction of often hands-off pastoral care and oppressive expectations Millar encountered in the Cofidis team contributed to leading him down a dark path.

Meanwhile, although the British success on the track was celebrated in those early years, the programme’s singular focus on the velodrome was also criticised. I was working for Cycling Weekly at the time and one of my jobs was to read and help select the readers’ letters for publication. Barely a week went by without someone – usually passionate and well-meaning – criticising Keen’s approach. People wrote things like: ‘Has anyone told Peter Keen that it’s all very well being the best in the world over one kilometre, but the Tour de France is 3,500 kilometres long,’ or ‘the banking at Manchester velodrome isn’t going to help anyone prepare for the Alps and Pyrenees.’

The nadir as far as the road racing enthusiasts were concerned was when British Cycling stopped sending a national team to the Tour de l’Avenir in 1999, partly because successive Great Britain teams in the 1990s had been given a pasting by their contemporaries on the top pro squads. The knives were really out at that point and everything got criticised – even the dayglo yellow Great Britain jerseys, chosen by Keen partly so the riders could find their teammates more easily in the peloton. I remember a reader with a cutting sense of humour writing in to say: ‘They don’t need a glow-in-the-dark jersey to find each other – they’re all at the back.’

The British riders who did make it tended to be lone wolves who found their way in spite of the lack of a system – Millar, Jeremy Hunt, Charly Wegelius, Roger Hammond. The Dave Rayner Fund was supporting more and more young riders to chase their dreams, providing the money and the contacts so they could go and get experience racing with an amateur club in Europe. Some riders did make it and earn professional contracts, but there was no system in place, no fall-back for those who had talent but didn’t quite make it first time round.

Ellingworth knew three key things that fuelled his vision. Firstly, it was that a lot of the young riders he spoke to, even those who were very good on the track, aspired to riding the Tour de France and Paris-Roubaix, and some of them would be lost to the sport if there was no obvious pathway on the road. Secondly, the skills and discipline that trackcraft gave a rider not only transferred well to the road but were critical if a rider was to thrive in the bustle of the peloton. And finally, he knew that living and racing abroad was not just about the bike. History was littered with tales of talented riders who couldn’t hack it because they couldn’t adapt to the language, the food or the lifestyle. Ellingworth had lived and raced in France, so he knew what it was like. He was determined that the Academy would give the riders skills they needed for life – how to organise not just their training but their day-to-day logistics; how to cook for themselves so they didn’t have to pack Rice Krispies and baked beans along with their shoes and bibshorts every time they went abroad; and a basic grasp of a foreign language. Life in the Academy was deliberately structured like a job, with a fixed start time (early in the morning), and a range of responsibilities on and off the bike. There was very little down time.

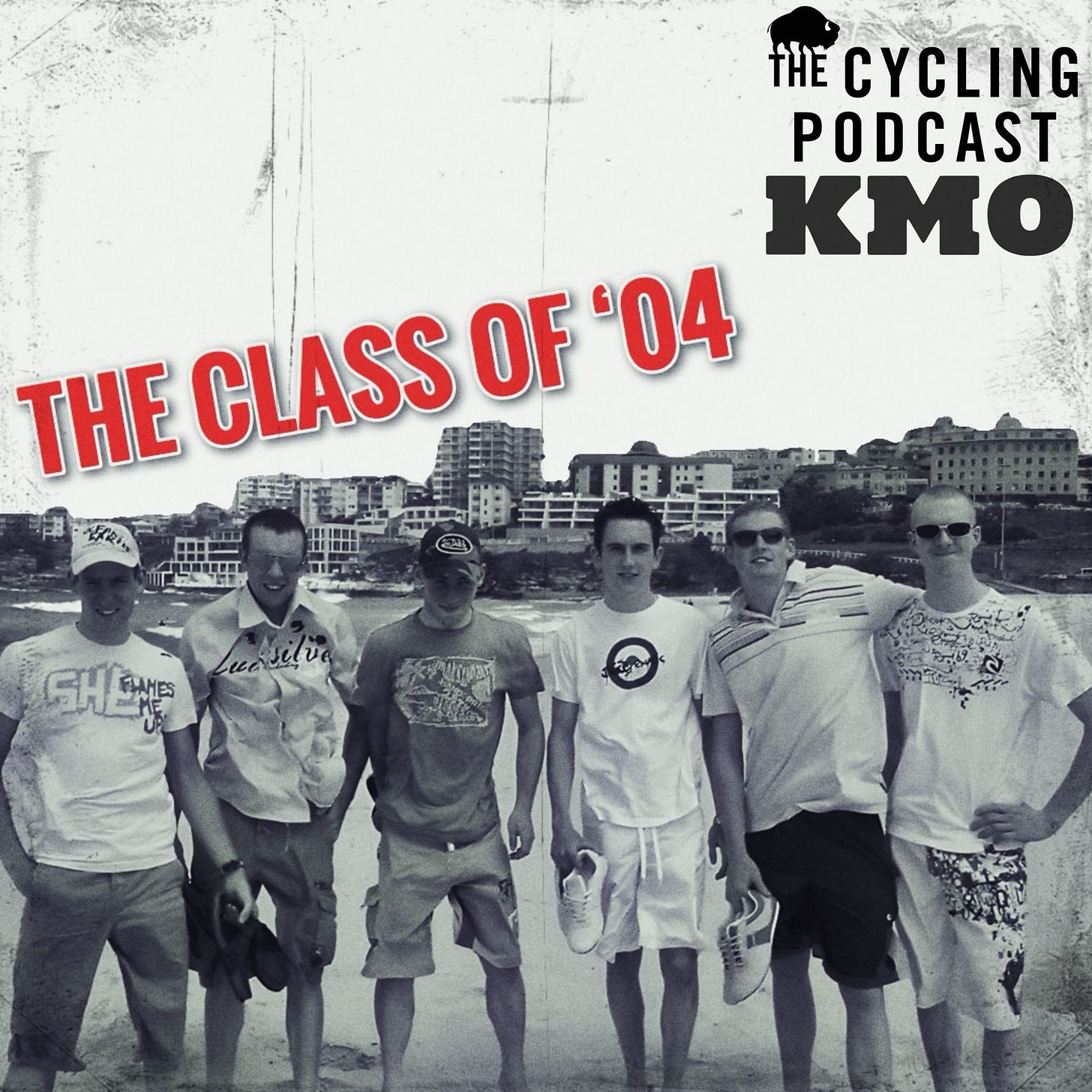

The Class of ’04 included Geraint Thomas, Mark Cavendish and Ed Clancy – a future Tour de France champion, the all-time record Tour de France stage winner, and a multiple Olympic champion. Between them they have enough rainbow jerseys to fill a large wardrobe. Of the other riders among that first intake, Matt Brammeier had a good pro career and is now senior endurance coach at British Cycling. Bruce Edgar, Tom White and Christian Varley made up the rest of the group.

It’s tempting to look back and think how lucky Ellingworth was that almost half of that first cohort turned out to be generational talents. But if we flip things round, how many talented riders in the generations that preceded them fell short not because they weren’t good enough but because they couldn’t call on the structure, systems and support the Academy offered?

Our episode, The Class of ’04, made by Daniel Friebe and Richard Abraham, is a bumper listen, running to more than two hours, but it is packed with stories of what the British Cycling Academy was like in those early days. We hear from Rod Ellingworth, Ed Clancy and Matt Brammeier but also from two riders who didn’t quite make the grade, Christian Varley, and Ross Reid, who was then Ross Sander, and who joined the Academy a little later but whose story is so compelling it demanded inclusion.

The Class of ’04 is the 17th episode released exclusively for Friends of the Podcast subscribers this year. An annual Friends of the Podcast subscription gives instant access to those 17 episodes plus a back catalogue of 300 KM0 episodes made over the past decade. The financial support from Friends of the Podcast is vital to us because it allows us to commit to free-to-air daily coverage of the grand tours every year.

It’s been a busy week at The Cycling Podcast with two regular episodes released as well as the Class of ’04.

We kicked off our Review of 2024 series, which will unfold over the coming weeks, with part one, Annus Mirabilis. Daniel Friebe, Rob Hatch and Richard Abraham look back at the 2024 racing season and weigh up the riders who had outstanding years. There’s a Slovenian fellow called Tadej who didn’t have a bad campaign, but who else impressed?

Rose Manley and Denny Gray are reunited with Orla Chennaoui for the latest episode of The Cycling Podcast Féminin, One Foot in the Gravel. It’s another packed episode as the team give their thoughts on the 2025 Tour de France Femmes route, which was unveiled in Paris last week. Then there’s discussion of the big transfers so far this off-season, with Demi Vollering’s blockbuster move from SD Worx to FDJ-Suez top of the bill. Finally, the segment that gave the episode its title, they cover gravel racing. Orla was in Leuven for the UCI World Championships, won by Marianne Vos, and we hear from last year’s world champion Kasia Niewiadoma about why more and more road racers are embracing their inner grit by taking on the discipline.

Cracking episode once again. Thanks team!

Looking forward to listening to this bumper episode over the coming days.