Mads Pedersen wins Tirana-Adriatico

After the Albanian grande partenza, the Giro d'Italia is about to resume on home soil

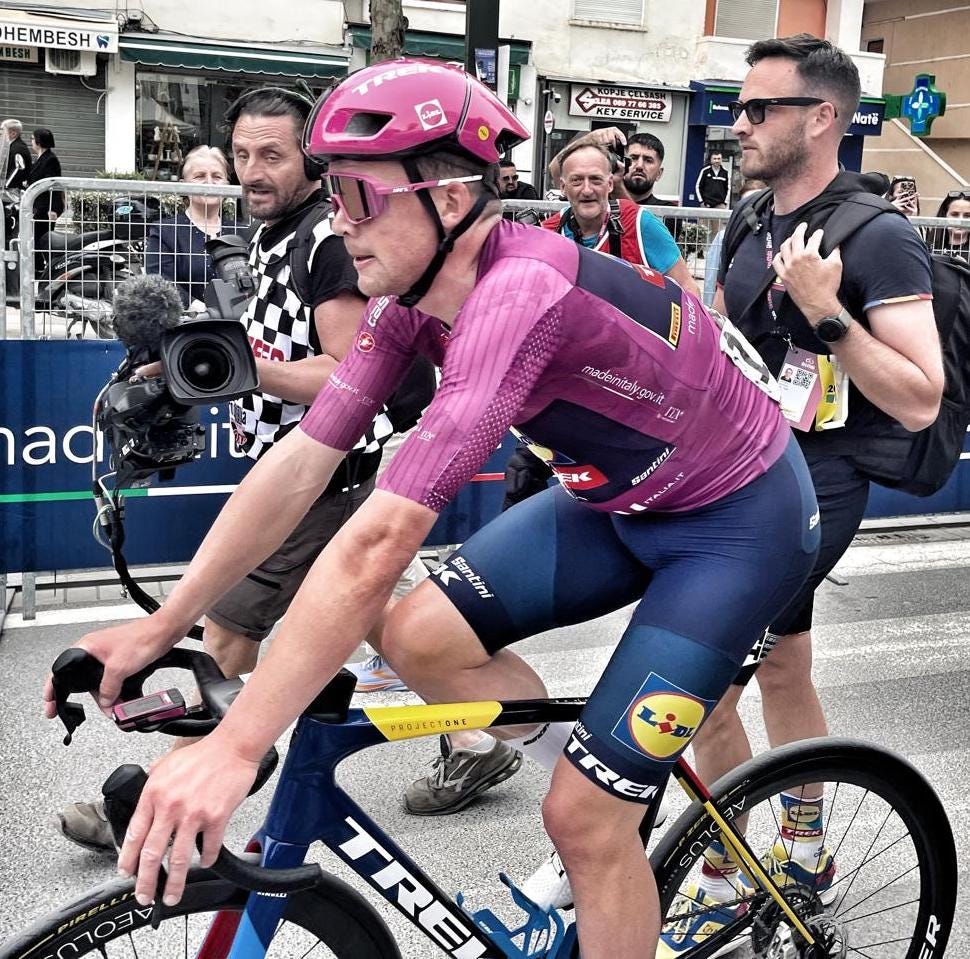

Mads Pedersen won Tirana-Adriatico emphatically, becoming the first Dane to wear the maglia rosa – and the second – winning two of the opening three stages and putting up such a great fight in the time trial that he was able to reclaim the race lead before the Giro headed across the sea back home to Italy.

The Tirana-Adriatico pun came to me too late for Sunday’s final Albanian episode, naturally, and the sticklers for detail would have pointed out that the Giro’s opening stage started in Durrës on the Adriatic coast anyway, but Adriatico-Adriatico doesn’t work and why let the facts get in the way of a half-decent play on words?

Had it not been for Tadej Pogačar and Mathieu van der Poel’s brilliance, Pedersen would have been hailed as the man of the spring, with a win at Gent-Wevelgem and a string of consistent, high placings. When a rider with his attributes is on such good form it can often look like every stage at a grand tour – bar the highest mountains – has his name on it. With at least three or four of the next few stages, including the ‘Strade Bianche’ stage on the gravel to Siena on Sunday, likely to suit him perfectly, he could dominate the Giro right up to the Tuscan time trial, especially as it’s not in the interests of Red Bull-Bora-Hansgrohe or UAE Team Emirates to do too much too soon.

Pedersen already has a couple of pairs of indestructible* underpants in his luggage, courtesy of the new maglia rosa sponsor Iuman. There’s a good chance he’ll add enough pairs to his collection he won’t need to do any rest day laundry.

*Possibly indestructible, we’re not sure.

Friday

We recorded at a bar in the square outside the national football stadium, built almost ten years ago replacing the old Qemal Stafa stadium. In the pre-Giro KM0 episode, Big Brother, Daniel and Professor John Foot talked about the complicated relationship between Italy and Albania and the football stadium’s history seemed to represent that story.

Just before the Second World War, Albania was occupied by Benito Mussolini’s Italy and the fascists set about developing the city rapidly. An Italian architect called Gherardo Bosio, part of the fascist government, was commissioned to design many of the buildings, including the stadium, and did so in the Rationalist style, using lots of square shapes and blocks of marble and white stone.

Work on the stadium began in August 1939, just weeks before war began to spread across Europe, and the first stone was laid by Italy’s foreign minister, and Mussolini’s son-in-law, Galeazzo Ciano. Construction was interrupted by the war, German occupation and Italy’s capitulation, and it wasn’t until 1946 that the Albanians finished it off, although they could only clad one side in marble rather than all four, as planned.

When the stadium finally opened in 1946, it was named after an Albanian hero, Qemal Stafa, one of the founder members of the Communist Party, who was assassinated by the occupying Italian fascists on the outskirts of Tirana on May 5, 1941. May 5 is a public holiday, Martyrs’ Day in Albania. So the stadium was conceived by Italian fascists but named after an Albanian communist. When they knocked it down to build the modern stadium, they kept a section of white stone wall near the main entrance.

Dinner in Tirana was at an Italian bar in our part of Tirana, the Blloku, or Block, which is now a trendy district but was once a gated private residential area for high-ranking communist party officials. We sat at high tables and the menu featured a Trump Tower Cheeseburger, which dampened expectations slightly. At least they were cycling fans, I thought, because surely the Trump burger was paying tribute to the late 1980s Tour de Trump stage race in the US… I had the sausage feast on the basis that the Albanian sausages I’d had in Durrës had been pretty decent - but these turned out to be greasy, salty hot dogs of synthetic pink meat in dry skin.

Our new signing, Pelacci arrived and we, rather unfairly, tested him on cycling history. He’s only 27, so very much a candidate for the press room’s white jersey and I felt very old when mention of Fignon was met with a quizzical expression. Daniel and I ran through the Tour and Giro winners in reverse chronological order, getting all the way back to the Second World War for the Tour, and the early 1960s for the Giro. We’d probably have got a bit further if we hadn’t been boring everyone at the table to tears. Pelacci told us all about his family’s Parma ham business and how to tell whether a leg of ham is from the left or the right. I looked down at the pink wieners on my plate and wondered which part of the animal they were from.

Saturday

Before the time trial got underway I went, on Larry Warbasse’s recommendation, to Bunk’Art2, a Cold War nuclear bunker that’s been turned into a museum telling the story of Albania’s modern history. It was a fascinating, if bleak, lesson in the country’s post-war authoritarianism under the dictatorship of Enver Hoxha.

The little concrete-walled rooms and narrow corridors were claustrophobic and the distant sound of an air-raid siren every now and then added to the general feeling of unease. In the 20 or so rooms there were displays which brought home the horror of a Communist dictatorship. Long lists of the thousands of victims of the regime, murdered or tortured for opposing the dictatorship in major and minor ways. Religion, political opposition or trying to escape Albania were among the most serious ‘crimes’. Even hairstyles and clothing were policed by the authorities to ensure they fitted in with a Communist ideal.

There were rooms dedicated to the state’s security services, or Sigurimi. Exhibits showed how photographs were manipulated for propaganda purposes and how civilian homes were bugged with microphones. Surveillance was one of the main industries of Albania with techniques and equipment imported from the Soviet Union and East Germany.

There was even a display of anonymous letters of dissent, posted at considerable risk to the writer, criticising Hoxha and the government. They were angry, funny, mocking and sometimes childish, all symptoms of being oppressed by an unflinching weakling obsessed with appearing strong.

Most chilling was a list of 36 different torture techniques used to break citizens during interrogation. Some of them were truly horrifying and surprising making me marvel at how some humans can devise such wicked cruelty. I’d been down in the bunker less than an hour but the claustrophobia was starting to make my shirt collar feel a little tight and the dim-lighting was playing tricks in front of my eyes. My black sense of humour wondered whether ‘watching a time trial’ counted as state-sanctioned torture.

My overwhelming takeaway of the bunker, especially after seeing the grim bedroom for the interior minister and the austere, wood-panelled office where, presumably, Government business would continue after the apocalypse, was that surviving armageddon would be a waste of time. Far better to perish immediately in a flash of light than cling on underground as the radiation seeps through the soil.

Albania built more than 175,000 nuclear bunkers, large and small, all over the country, such was Hoxha’s paranoia. Albania was not part of the Soviet block so Hoxha feared attack from both East and West. He died in 1985 just before Bernard Hinault won the Giro, not that the two events are in any way related. Communism finally fell in 1991, when Franco Chioccioli won the pink jersey at the Giro. Both these races feel recent to me, part of the sport’s technicolour era, even if they are ancient history in cycling’s timeline. It was strange to me, wandering around the streets of Tirana, seeing people my age, realising that many of them didn’t find out the Berlin Wall had fallen until weeks later, such was Albania cut off from the rest of the world.

* * *

The ongoing battle to tell the story of Norman Wisdom’s bewildering popularity in Albania was doomed to failure. Perhaps Daniel is scarred by childhood memories of rainy British afternoons stuck indoors in front of the telly. When I was growing up it did seem like Wisdom’s films, mostly made in the 1950s and 1960s, were on a lot. They weren’t my cup of tea either, with the pratfalls, gurning, silly hat and his high-pitched soundbite, ‘Mr Grimsdale’.

Hoxha, who banned almost all Western films, books and music during his four-decade rein between the Second World War and his death in 1985, was a big fan of Norman Wisdom’s films and they were shown a lot in Albania for years, making him the country’s most popular movie star – although everyone knew him as Mr Pitkin, the name of the character in one of his film series. When England played Albania in a World Cup qualifier in Tirana in 2001, Wisdom was the guest of honour and he took to the pitch at half-time in a half-England, half-Albania shirt to a rapturous reception. He was even more popular than David Beckham, the England captain at the time. He even appeared on an Albanian stamp after he died.

Apparently Hoxha liked Wisdom’s films partly because he found them funny but also because the Mr Pitkin character represented the underdog, always under the boot of his aristocratic and capitalist bosses. Ironic really.

I almost asked Producer Jon to play out Sunday’s episode with a montage of Wisdom clips without telling Daniel, but decided that would be going against team orders too early in the Giro.

Our hotel for the night was a incongruously luxurious place perched on a hill overlooking the plains below. The fixtures and fittings were befitting a five-star hotel but the evening meal fell well short of that. The Albanian byrek, flaky pastry parcels filled with feta and spinach, weren’t available, nor was the goat, which Daniel had his eyes on, so we opted for the wood-fired lamb. My plate was pretty horrific to look at – a huge chunk of fractured bone and a bulbous joint, connective tissues, ligaments and gristle. There was some meat among the wreckage but it was like excavating Roman ruins trying to find the edible bits. I needed Pelacci to tell me what I was looking at. The wine was good, so there was that.

Sunday

The TV coverage all weekend didn’t quite match my own experiences of Albania. Put it this way, the cameras showed the country’s best side and shied away from some of the scruffy realities. The Giro’s host broadcaster, RAI, kept their punditry team in Lecce on the other side of the sea and it felt like there was a conscious attempt to keep the camera at arm’s length.

All countries have good and bad, rich and poor, and part of the deal is that the race’s visit is used to show the best side, but as we headed to the airport I reflected on the weekend and felt conflicted.

The Giro didn’t exactly bring the party to Albania. There was no publicity caravan, for example, and – even compared to Israel in 2018 and Hungary in 2022 – it felt like the race just wanted to get through the opening three days and get back to Italy without major incident. There were, fortunately, only two riders who failed to get through unscathed. Soudal-Quick Step’s leader, Mikel Landa and Geoffrey Bouchard of Decathlon-AG2R both crashed out on the opening day. A very costly loss for Soudal, who lost their podium hopeful and had to reconfigure their entire strategy after less than four hours of racing.

Crashes can happen anywhere, of course, and the roads were certainly not as bad as feared, but Tom Pidcock’s comment to Daniel about not taking risks on the big descent on Sunday because he didn’t want to end up in an Albanian hospital possibly summed up the mood of the peloton.

There will be the usual post-race reports of how much money will flood into the Albanian economy as a result of the Giro’s visit but my sense of unease was at seeing the roughest parts of the country with broken roads and decaying housing, people sitting on the pavement roasting sweetcorns for money, sometimes no pavement at all, and piles of rubbish, stray dogs and cats, and realising that the Giro wasn’t really offering anything to the people of Albania.

Elite sport, with its millionaire athletes and a hose pipe permanently hooked up to suck up resources, sometimes gives the impression that it turns up, taking what it needs, and clearing off again leaving someone else to put the barriers away and deflate the giant inflatable underpants. The riders aren’t responsible, of course, they go where they’re told, but my impression of the weekend was that it was a marriage of convenience, perhaps with a darker political motive behind it. We’re not quite sure of the agreement between Italy and Albania but discussions started over coming to an arrangement to use Albania as a base to process immigrants arriving in Sicily from Africa. That was shelved after a backlash in Italy. The fallout from that possibly contributed to the announcement of the Giro route, usually made in October, being delayed until January. Either way, the bottom line is that the Giro visited in Albania for precisely that reason, the bottom line.

It’s not that I didn’t find the trip fascinating and the people warm and friendly. The crowds for the cycling were small but those who were watching were enthusiastic. The juxtaposition between the Cold War architecture and the modern day symbols of Western wealth was interesting. But the gentrification of one street just around the corner from another that looked on the verge of collapse suggested that it would take billions of dollars to transform Albania and while the Giro’s visit might have contributed a little to increasing the country’s profile and changing perceptions, the impression left was almost translucent. As for the Giro’s legacy, well, they came, they raced around and they went home again.

• A big thank you to all The Cycling Podcast listeners who spotted us and came to say hello over the course of the weekend, starting at Stansted airport last Thursday.

KM0: Greek Mythology

Our latest episode of KM0 for Friends of the Podcast subscribers is called Greek Mythology and looks back at the 1996 grande partenza in Athens, held to celebrate the centenary of the modern Olympic Games and La Gazzetta dello Sport, the Giro d’Italia’s founding newspaper.

On Monday, as the 2025 Giro crossed the Adriatic after three days in Albania, it mimicked the journey made by the Corsa Rosa 29 years ago.

On that occasion, no one could honestly call the overseas grande partenza a great success. The tryptique of stages was marred by crashes, threadbare attendances and strike threats by the riders. The worst or most infamous was also yet to come, when the race convoy headed back to Italy and should have been greeted in Puglia by the Italian drugs squad. In this episode, we tell the story how an even more shocking police sting than the Festina scandal (which happened two years later) was averted, and what happened next.

Arrivée: Vuelta Femenina

Rose Manley and Rebecca Charlton look back at the first grand tour of the year for the women’s peloton, the Vuelta Femenina.

The race marks the first World Tour stage race to see top rivals Anna Van der Breggen and Demi Vollering go head-to-head. Vollering may have had the edge so far this season but Van der Breggen has found further form since her comeback. Then there’s fellow SD Worx alumnus Marlen Reusser who separated the two Dutch rivals on the podium at Setmana Valenciana earlier in the year. So where will the fabled red jersey land this time?

Great write-up, particularly your reflections on the 'so what'. I cycled through Albania in 2018 and didn't really see the glossy bits, but was very pleasantly surprised. Most of the Balkans is rather scruffy, but I've found Albanians the most courteous and welcoming people. I found a lot to like and admire there, and seeing the Gracen Pass again was a delight. Anyway, disaster averted for most, now for the main show!

Brilliant write up Lionel. Compliments the Pods and KM0s.