Arrivederci, dear Gianni

Daniel pays tribute to his friend, Il Principe, Gianni Savio, who passed away a few days ago aged 76

Today (Thursday) Gianni Savio’s funeral will take place at the Gran Madre church in Turin, the city of his birth. For years he was a cherished fixture in The Cycling Podcast’s Giro d’Italia coverage, and, for that reason, we wanted to pay our own tribute.

LISTEN: Il Principe, an episode of KM0 originally released for Friends of the Podcast during the 2018 Giro d’Italia

by Daniel Friebe

I spent the whole of Monday fearing the moment, an ending was nigh. A couple of days earlier, Ciro Scognamiglio of La Gazzetta dello Sport had texted to say that he’d tried to message Gianni and that Gianni's daughter, Nicoletta, had replied that he was in a bad way. I’d then sent my own text, to which Nicoletta responded in terms that sounded bleak, possibly hopeless.

We'd last spoken a few weeks ago. His greeting had been the same as always – the same ‘Caro Daniel!’ that was the starting klaxon for all of our conversations on the phone, probably hundreds of them over 20 years. Gianni had been laid low, in fact housebound for a year and a half by this point. A series of falls while jogging – he and I disagreed on the number – had apparently been caused by an accumulation of fluid on the brain, and it’d taken months to both heal from the injuries and establish why he kept losing balance. He’d been living in a ‘golden prison’, he kept saying, spoiled and fussed over by his beloved wife, Paola and daughters Nicoletta and Annalisa, but also confined in the misery of inactivity. ‘Figurati – per un uomo di sport come me!’ – ‘Imagine, for a man of sport, like me!’

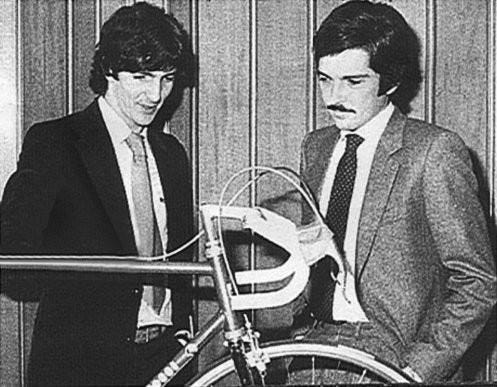

‘A man of sport.’ A clunky translation, perhaps, but the one Gianni chose himself, in the English for which he was forever apologising. ‘Sai, io vengo dal calcio…’ - ‘You know, I come from football…’ was another favourite preface, and indeed a true story, for Gianni had played at a decent level in his youth. Among his proudest claims to fame: man-marking future World Cup winner and golden boot winner Paolo Rossi in a match in the 1970s. Football was his first love, but cycling his ‘maledetta passione’ – his ‘damned passion’ as he used to call it, contracted from his maternal grandfather, Giovanni Galli, an Italian champion early in the 20th century. The family name had survived through a business, a manufacturer of brakes and components – a scrappier, smalltown Campagnolo, if you will – and this had provided Gianni’s route into sponsorship and, soon thereafter, team management in the mid-1980s.

I could list some of the riders Gianni launched or unearthed – tell you that no one but him believed in Andrea Tafi or would take a punt on Nélson Cacaito Rodríguez, conqueror of Val Thorens in the 1994 Tour de France. But the best available testament to those early years is perhaps served here, in the thousands of images capturing a sport and world that no longer exist, and a man whose spirit and warmth imbued them: Gianni Savio photo gallery on Sirotti.

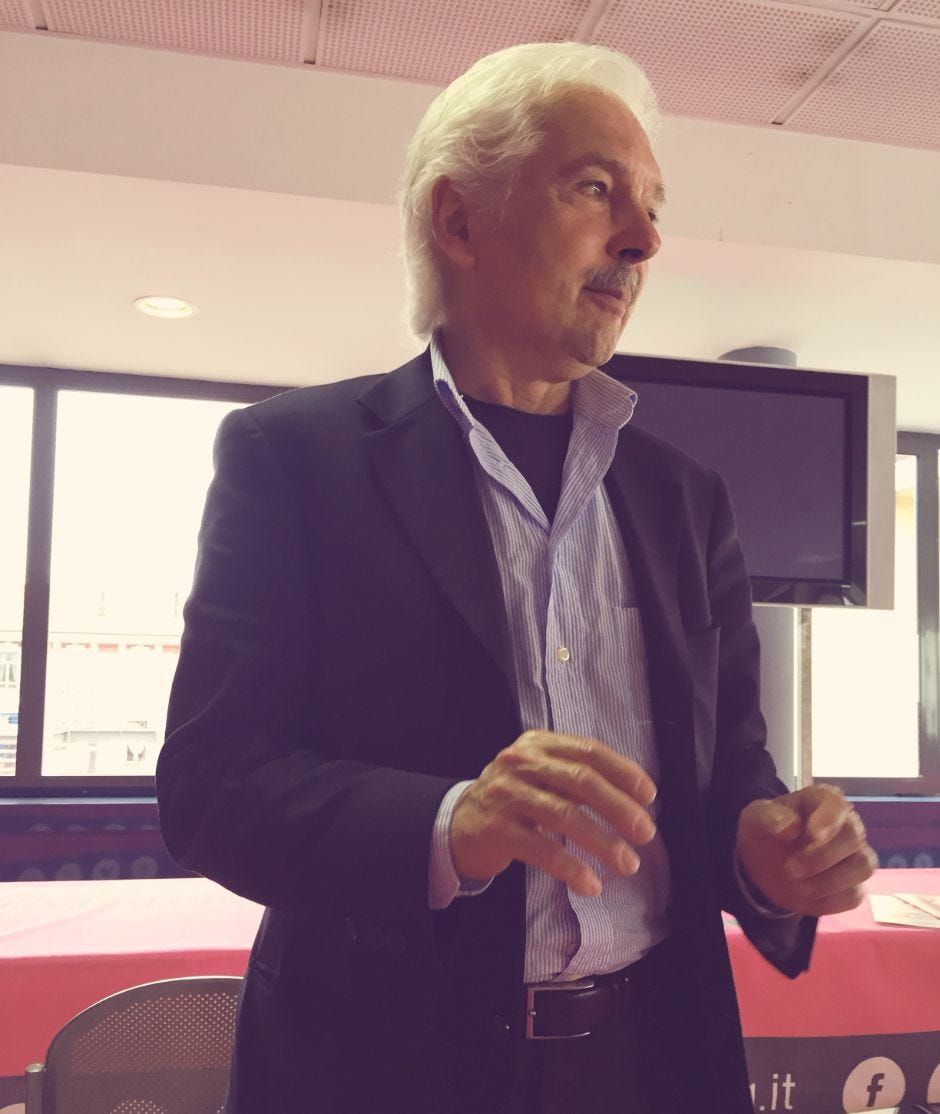

Gianni himself would smile at such nostalgic indulgence. In the brief hours since his passing, I’ve replayed dozens of our conversations, remembered hundreds of his bons mots, and been struck that, even after forty years in the game, he would rarely if ever lapse into wistful remembrance. The suits and silk scarves, that straight-backed, almost courtly air – quintessentially Piedmontese – had earned him a nickname, ‘Il Principe’ or ‘The Prince,’ a moustachioed monarch among the denim-wearing denizens of team bus carparks. More curious to me, though, was that Gianni invariably completed the ensemble with footwear, usually Adidas or New Balance, that was built for speed – as showcased by his iconic, unerring scuttle up the finish-line in San Giovanni Rotondo after Fausto Masnada’s Giro stage win in 2019.

That small detail seems to me now to say or symbolize a lot: Gianni had survived so long – and most of the time that’s what it was, a scramble to stay alive – precisely because he had remained in constant motion, on the tips of his toes. UK-based readers will be familiar with one of the more famous catchphrases of the hit 1980s sitcom, Only Fools And Horses, Del Boy's ‘Next year, Rodney, we’ll be millionaires!’ Well, Gianni would tell me and everyone else his own version of that: ‘We’ve got a big sponsor who is interested in coming on board, so we can become a really big team…’ You could think he was deluded, especially after hearing it for the eighth year in a row, only for the new season’s jersey to appear, wallpapered with twenty-odd barely legible logos like ‘Guavaberry Golf’, or for his latest intake of riders to consist of more thirty-something misfits and Latin American moonshots. But Gianni’s confidence and determination never seemed to flag. He allowed neither his ideas nor his passion to become outdated, decayed, dog-eared by cynicism. He was acutely aware of the raised eyebrows. Attuned to the inevitable sniggers. But what slight is scorn to a man who is also the first to laugh at himself, as Gianni always was?

There was a time when, who knows, maybe he could have outgrown the ranks of the underdogs. I think I first interviewed Gianni in 2004. This was cycling’s lawless age of rogues and banditos. Gianni’s own teams had also had their fair share of positive tests and dishonourable mentions in police investigations. He would discuss these matters with a moral ambivalence that, giving him the benefit of the doubt, I translated as the rugged realism of someone who knew, had seen at first hand how high the stakes could be for riders he had sometimes plucked, in his words, ‘from tiny pueblos in the Andes’. In short, the worldview of someone too empathetic to be evangelical, or too long-in-the-tooth for facile hypocrisies. That was my sense. Or maybe my hope.

Sometimes I’d be assailed by doubts, hounded by professional guilt and ask riders or other ‘informed parties’. ‘But, Savio…these allegations…’ And the responses would be broadly reassuring. Of course there are those who’ll legitimately say I asked the wrong people or wrong questions. That snow white was eventually the colour of his hair but not his conscience or way of doing business. That imposing a statute of limitations – basically assuming that for a period in cycling astride the 90s and 2000s nearly everyone’s closet rattled, and that ‘time is a gentleman’, to use a phrase he often employed – was the work of a judge and not a journalist. An objection to which I can offer no defence.

But, no, his teams never did quite join the superpowers – and perhaps this was one reason why. ‘I’ve never trusted anyone who's claimed to be the flag-bearer for anti-doping!’ he'd intone, probably while knowing that just such a position, with his gift of the gab, would have been the failsafe way to make bank. But also, possibly, a waypoint en route to other compromises that he wouldn't entertain, a cul-de-sac in which his impish, romantic essence couldn't be contained.

At around about the same time – mid-noughties or thereabouts – I proposed to Gianni that he write a monthly column for Procycling magazine. By then he had fully embraced and, to a certain extent, embroidered a coquettish, larger-than-life persona in the Italian media, and I didn't have to explain or spell out that I wanted to introduce an English-speaking audience to more of the same. The column ended up being a fixture for several years. The accompanying monthly ritual would consist of me dialling his number, waiting a few seconds to hear my resounding ‘Caro Daniel!’ cue – sometimes above the din of a finish-line announcer at the Vuelta al Táchira, or the not-so-distant throb of a Caracas street fiesta – and then off we would go: I would propose a subject, with no warning or contextualizing instruction, and Gianni would duly hold forth for approximately half an hour, pausing only to weigh up his pay-off line. ‘As we often say, the mother of imbeciles is always pregnant!’ was a classic to which we returned a little too often.

And so it went. Month after month. Year after year. Sometimes Gianni would report delightedly that he'd been complimented on his column by fans at the Tour of Langkawi, or asked to sign a copy by an English expat in a supermarket in Santiago. We never paid him and he didn't ask. There was no need to establish rules of engagement which for both parties went without saying.

Defining what those parameters were from today’s vantage point is a little more difficult, though only a little. Without knowing it, I'd latched onto Gianni because he embodied much of what had drawn me to a bizarre, little-known extremity of the sporting galaxy from the alien planet of the United Kingdom in the 1990s: the way it married exoticism and provincialism, grandiosity and humility, the romantic with the pragmatic. Its humour and unwillingness to grow up or abandon the fantasies of youth. Gianni personified, positively radiated all of this. In common, we shared the implicit recognition that we were lucky to have been infected and be living with that same ‘maledetta passione’.

More years passed. The 'big sponsor' still didn't materialize, but victories did, including at the Giro. The Corsa Rosa was, of course, Gianni in his element, his Mardi Gras. Every morning he would give his riders their orders – announce the day's ‘modulo’ or formation, who was the ‘bomber’ and who had been assigned the roles of ‘sweeper,’ ‘regista’ and so on, confusing sports but hopefully not his audience. He'd sign off by reminding them all to be ‘cattivi e determinati,’ ‘mean and determined,’ before emerging into the sunlight, beaming, for his glad-handing morning promenade towards the sign-on podium, interrupted every few seconds by another wave or thumbs-up – his smile widening, whiskers glinting – and another gleeful ‘Ciaooooo!’

On Tuesday night, another friend and travelling companion, the Italian writer Leonardo Piccione, tweeted: ‘If you ask me to name the person who, better than anyone else, has encapsulated and epitomised the 'spirit' of the Giro d'Italia in the years I've been following the race from the inside – the passion, romanticism, the lightness, the exuberance and the enthusiasm – my answer is and has always been the same: Gianni Savio.’

Needless to say that I would concur – and that, similarly, if you asked me to pinpoint a moment of the Giro’s quotidian pageantry that summed up the spirit of Gianni, it would be the end of the day, when he would appear in the pressroom and offer his insights from the stage to any of the few dozen or so of us typing up our daily dispatches. No other team manager, in my experience, had observed a similar ritual before and none has since. A sort of evening communion in the church of the Giro, with Gianni its unobtrusive but effervescent priest, his cologne its holy water.

The Giro was also where Gianni 'premiered' on The Cycling Podcast. I'd left Procycling at roughly the start of the Team Sky era, and the podcast quickly became a serviceable side hustle, so much so that in 2016 we recorded daily episodes from the Giro, on the ground. Without me ever fully briefing Gianni on what it, our 'show' was, and without him ever seeming to really care, he would talk into my microphone at nearly every start and finish, in Italian or English if I could twist his arm. He may not have realised it, but the medium fitted him like one of his pin-striped blazers – with that voice behind which you could almost hear the mischief in his eye, and a way of pronouncing every syllable or even letter as though he was making a downpayment on a mortgage. ’T-r-a-g-u-a-r-d-o V-o-l-a-n-t-e.’ ‘G-r-a-n P-r-e-m-i-o d-e-l-l-a M-o-n-t-a-g-n-a.’ Or, the day I put ‘Born to Run’ over the video of him scampering to congratulate Masnada, ‘B-r-u-c-e S-p-r-i-n-g-s-t-e-e-n!’

This was also the period when Gianni was cooking up his biggest talent-scouting coup. The story of how Egan Bernal had been discovered was actually a convoluted one involving several individuals, a catalogue of anecdotes. Gianni's own version of events would inevitably begin with a five-word sermon that I'd heard before from him for other South American niños maravilla, from José Rujano to Fábio Duarte: ‘Segnati questo nome – write down this name: E-g-a-n B-e-r-n-a-l’. The difference this time being the postscript: Bernal's transfer to Sky and a reportedly hefty payout for Gianni, followed two years later by the first Colombian victory in the Tour de France.

‘It won't change my life!’ Gianni would assure me with a chuckle when I ribbed him about his ‘Brailsford bonus.’ But the world was about to change, with Covid, just as cycling was lurching ever further into the realm of oligarchs and sportwashing nation states. Gianni's latest, as it turned out pretty much final Hail Mary was a partnership with a Spanish drone-manufacturing start-up, and for a brief period it sounded truly as though the eternal promise, his ‘Next year, caro Daniel…’ might finally become reality. Alas, the flying robots hit turbulence, ran out of money, and it was all Gianni could do to keep his underfunded, underpowered fuselage airborne.

He was now past 70. Those falls on his morning trot around the block – however many it was – could no longer be easily shaken or laughed off. He cracked his ribs and was suddenly under strict orders not to leave the house until doctors and physios ordained that the injuries had healed. But that was in 2023. Months later he was still trapped in that ‘golden cage.’ How’s it looking, I'd ask, and he'd reply bluntly: ‘Male, molto male, caro Daniel – bad, very bad.’ The 2024 Giro was starting in Turin, practically going past his house perched on the hill above the Po, across the river from the Mole Antonelliana, the city's most famous landmark. It was a travesty that he wouldn't be at the race in any year, but especially this one. That the circus was leaving town without its ringmaster.

Brian Nygaard and I tried to remedy that injustice by visiting him on the Sunday, as we were also beginning our three-week adventure. He was severely diminished – even Tadej Pogačar would be, after a year of shuffling or being wheeled from his bedroom to an armchair – but still smiling, in spite of everything. Still confident that the nightmare would soon be over. That he'd be himself again – not that his light had completely dimmed. Of course, comebacks were another Gianni specialty – what he'd done for Gilberto Simoni, Michele Scarponi and others, he'd now just have to do for himself.

LISTEN: Daniel and Brian visit Gianni at home during the 2024 Giro d’Italia

I was back in Turin for the Tour in July, when Biniam Girmay won. I called him as we drove away from the finish that day, in a rainstorm so violent I could barely make out the ‘Caro Daniel!’ He was doing better, he said. Not yet well, but better. The doctors thought they'd identified the problem, and he'd soon have surgery. Again, it felt like a heresy that a bike race had arrived in his fief and that Gianni was not in attendance.

Then, during the Vuelta, another message, when I’d phoned to say that I was there with one of his queridos former riders, Luis Ángel Maté, and we were both thinking of him. He’d missed the call but replied a few minutes later with a ‘grande abbraccio’ – a ‘big hug’ of his own, to both of us, and a ‘See you soon.’

And, finally, the last call in October, with him telling me much the same as what he had in July – that, at last, they'd found the problem. It'd soon be sorted. There was light at the end of the tunnel.

Between that and a few days ago I’m not sure what happened. Just that, suddenly we have no phone calls to look forward to, no modulo on Giro mornings. Only memories.

Of a day I spent in the passenger seat of a Selle Italia team car in a Dolomite stage in 2006, with him growling at his riders over the intercom to dig in against ‘chi ci vuole male’ – all the team’s haters and enemies, real or imagined. Of the time I aggravated Simoni so much in an interview that Gianni had to be sent on a diplomatic mission to retrieve him. Of the plan his team once had to make his moustache their emblem – like the logo on Bialetti moka pots – which sadly never came to fruition. Of the occasion, during lockdown, when he told me he’d been tone deaf in school, actually forbidden by the teachers from singing – and then a few days later, he’d sent a brilliant and touching karaoke rendition, a duet with Paola, of ‘Bella Ciao,’ the Italian anthem of freedom, recorded with a phone on their balcony.

Of standing with him behind the finish-line on the Passo Fedaia in 2022, each of us glued to a TV monitor, the Giro’s GC playing out, with his rider Edoardo Zardini somewhere down the road, trying to win the stage, and me telling him that, respectfully, Gianni, no one gave a f**k about the break. How he turned to me in mock disgust, arms flung in the air, and then we both collapsed in giggles.

All those moments, more that don’t come to me now but will later, and especially those laughs.

This was a brutal week for sport in Italy and particularly Turin because another of the ‘Magic City’s’ treasured sons, sports writer Gian Paolo Ormezzano, also passed away. A vignette from Fausto Coppi’s funeral had earned ‘GPO’ his break in journalism in 1960, and on Monday it was his own turn to – as he’d written of Coppi - take ‘his final walk, the most important of his life.’

That day, in Castellania, Ormezzano had observed, ‘no one among the mourners was ashamed of their tears, and in fact their sadness made them proud.’

Gianni Savio ends his earthly journey today in the same city where it began in 1948, surrounded by friends and family. The sadness will lessen with time but their pride at having shared a stretch of road will remain, together with an unfillable void.

Gianni Savio 1948-2024

Heartfelt and Beautiful ❤️

A beautifully fitting tribute, Daniel. Thank you very much for sharing. Gianni’s character shone larger than life through the podcast over the years, it truly was the perfect medium for him.

I was honoured to spend a couple of hours with Nicoletta in Turin at last year’s Giro. Her warmth and passion for both the sport and their community was no doubt a credit to her father. My thoughts are with all those who knew Gianni, RIP.